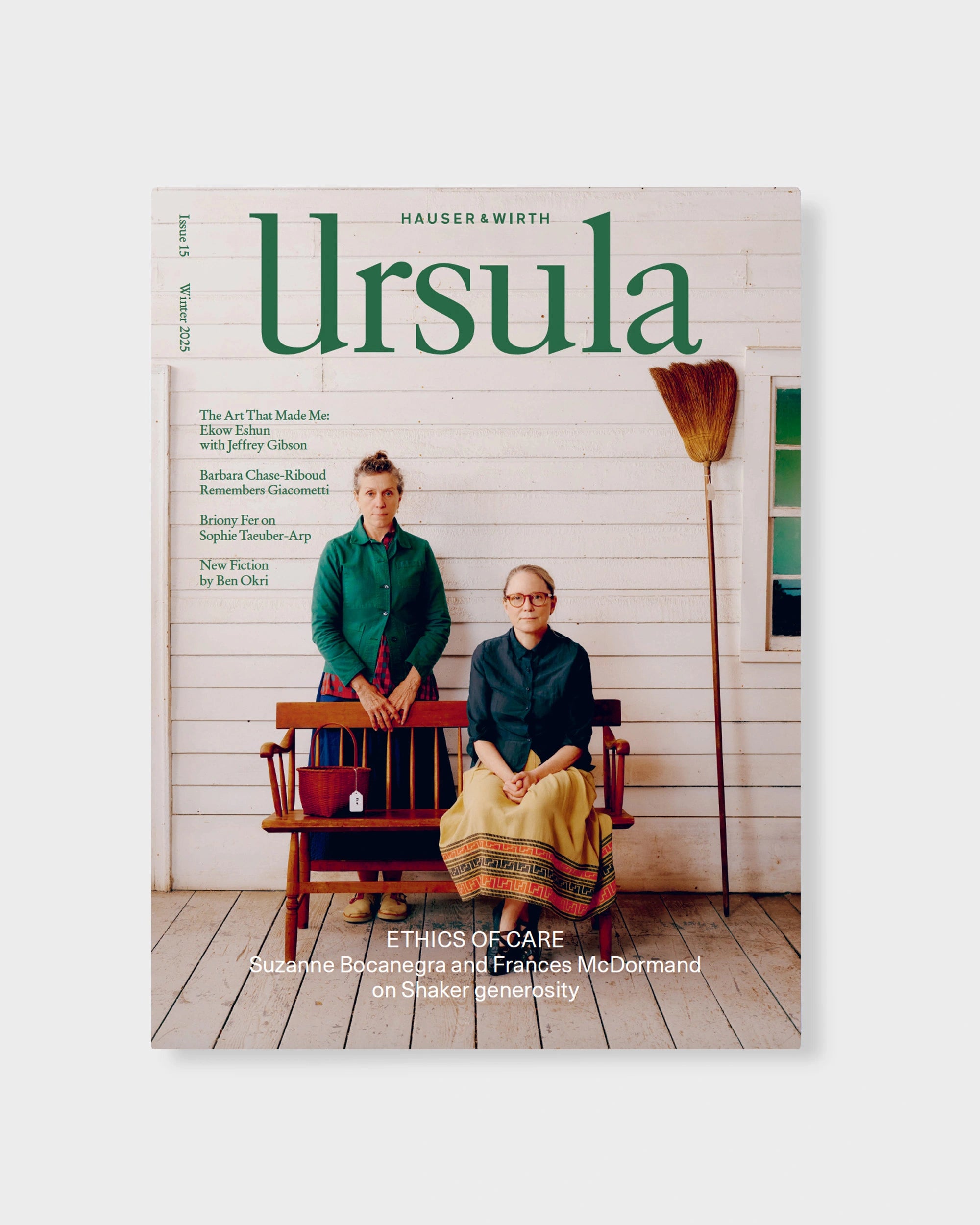

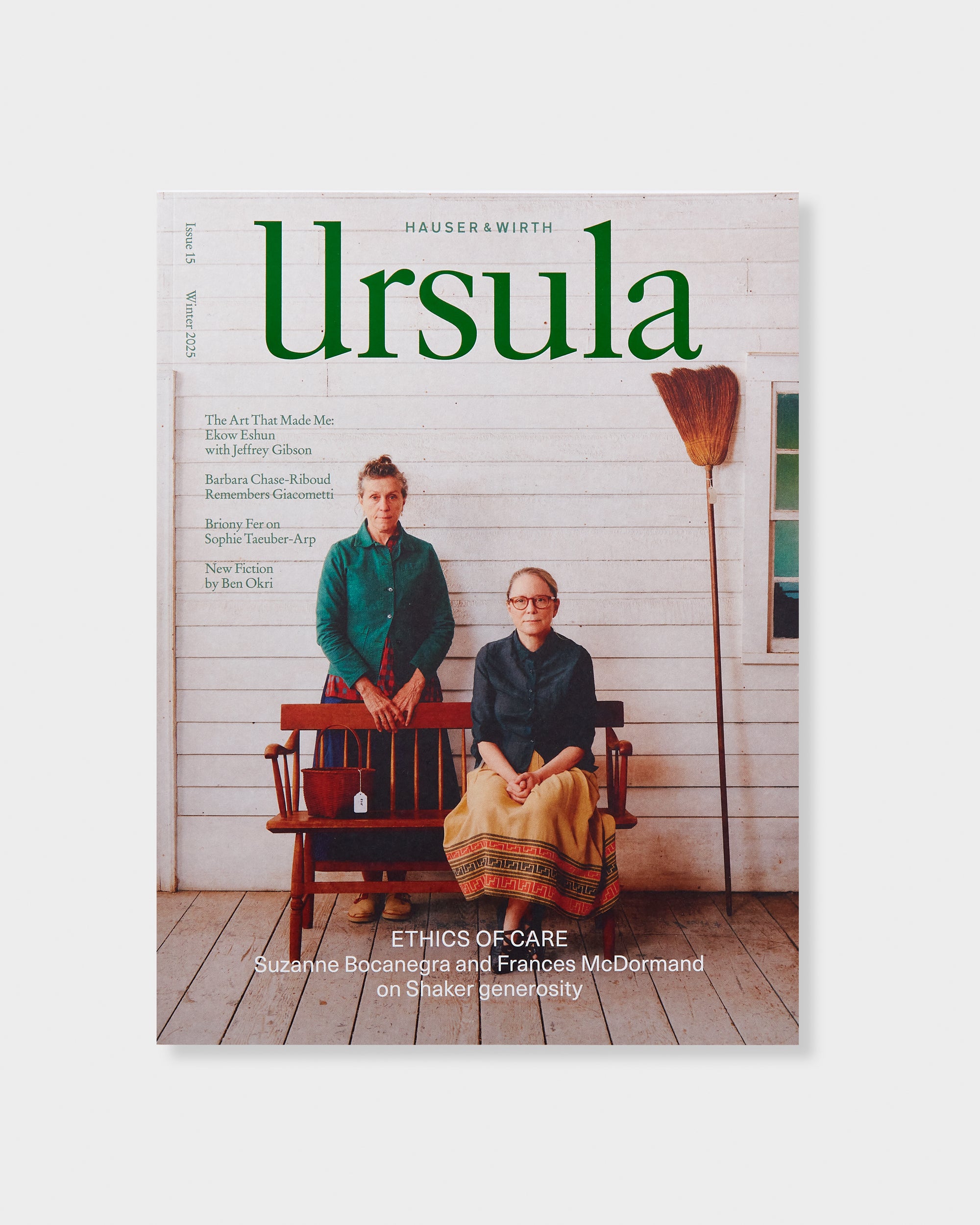

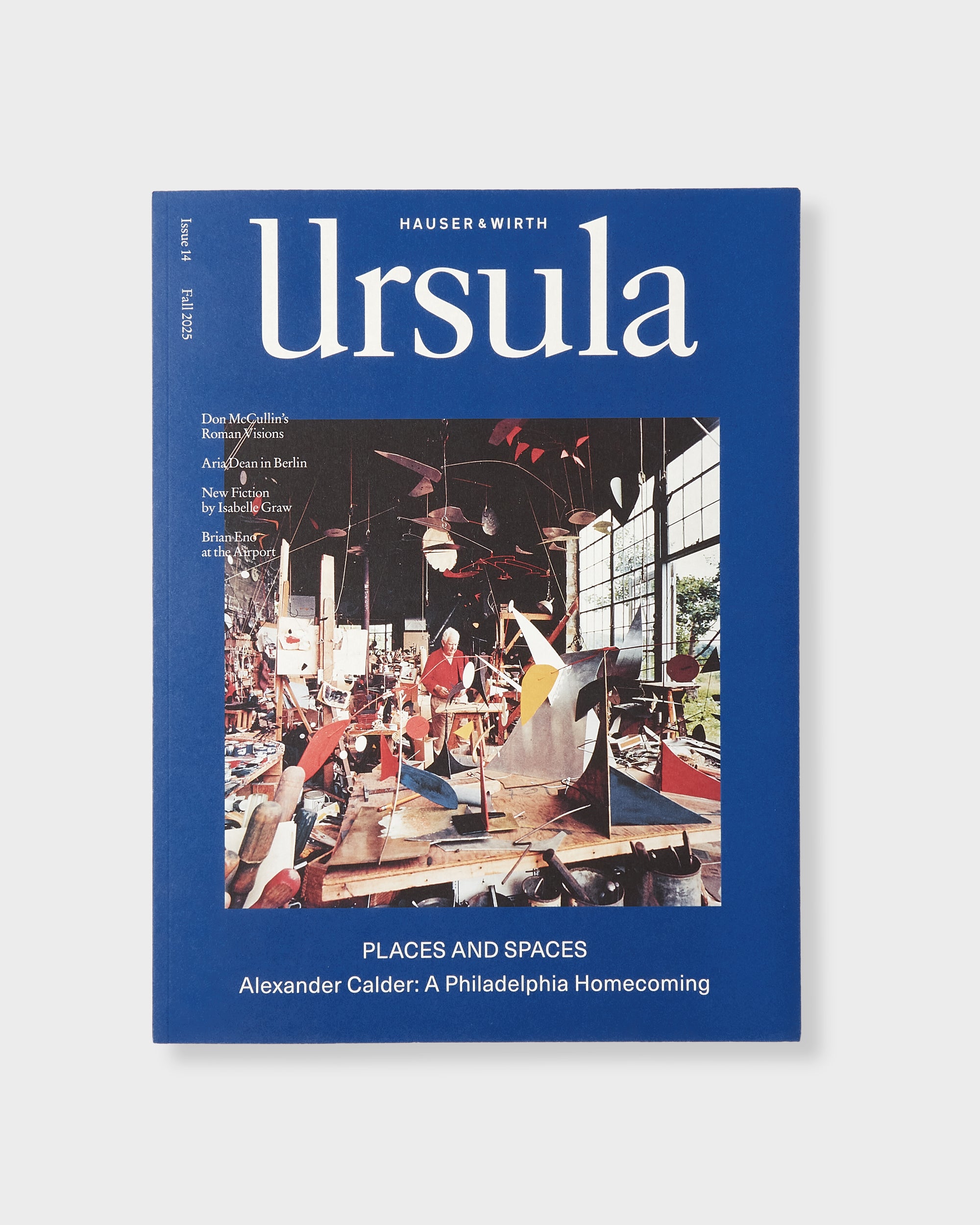

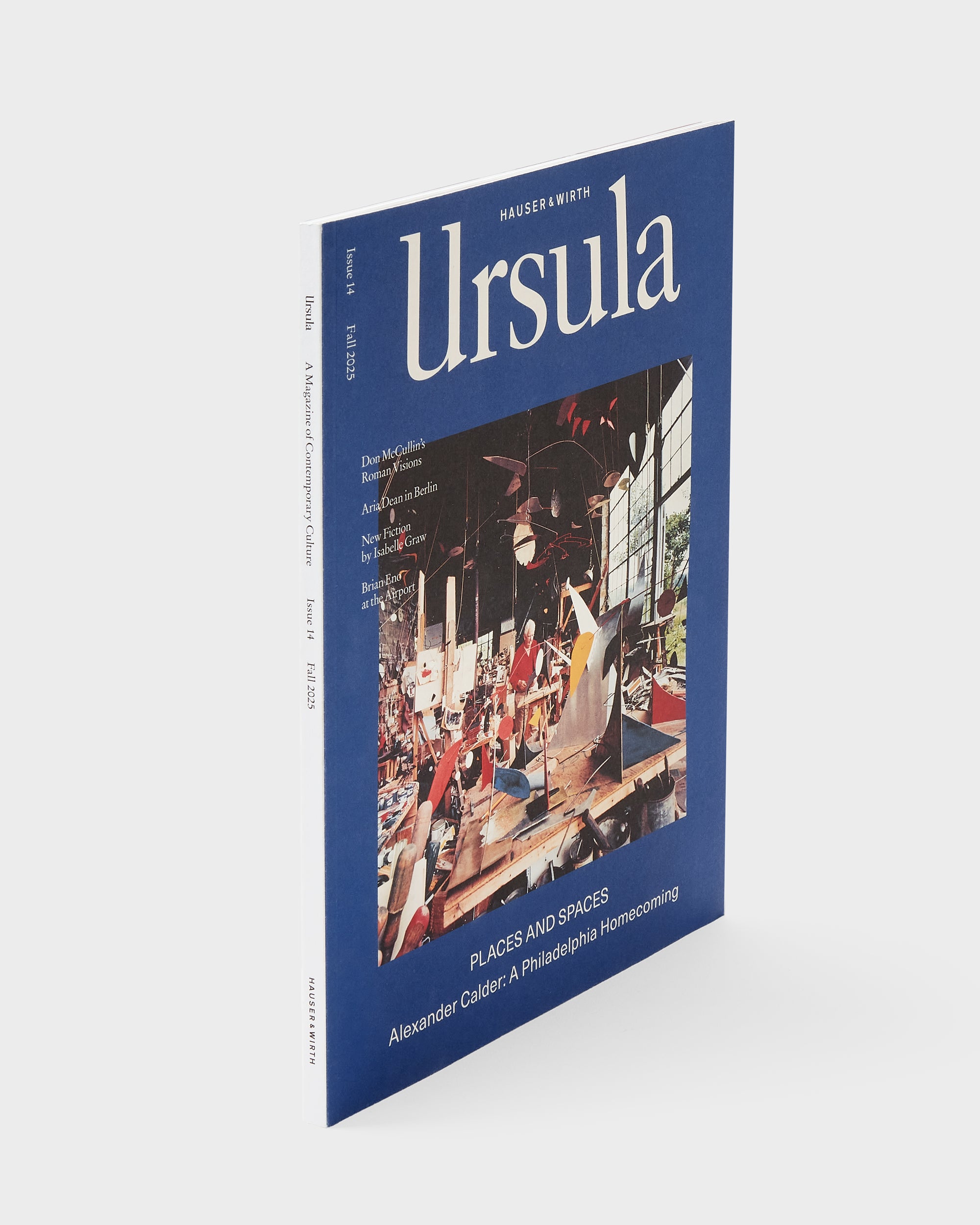

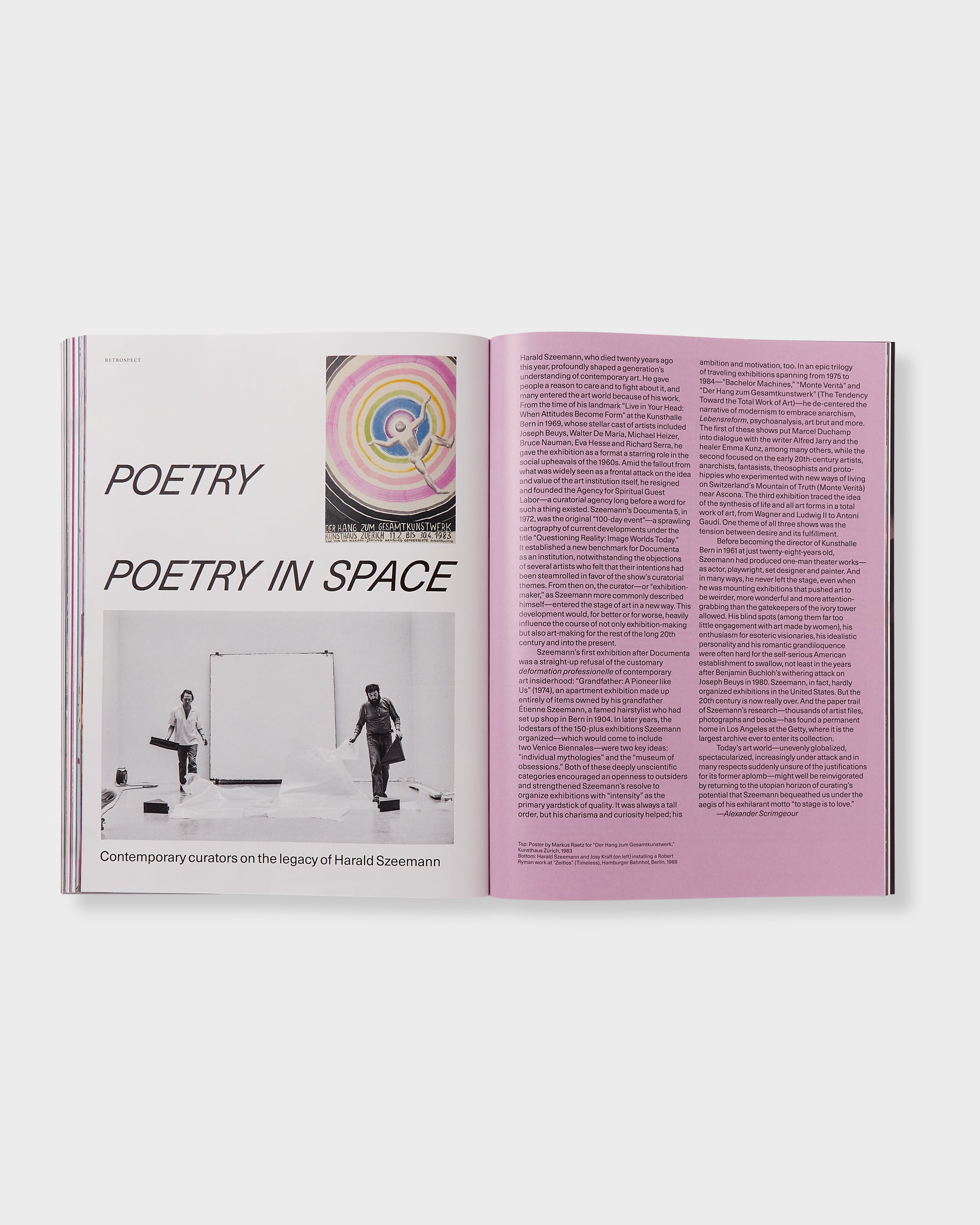

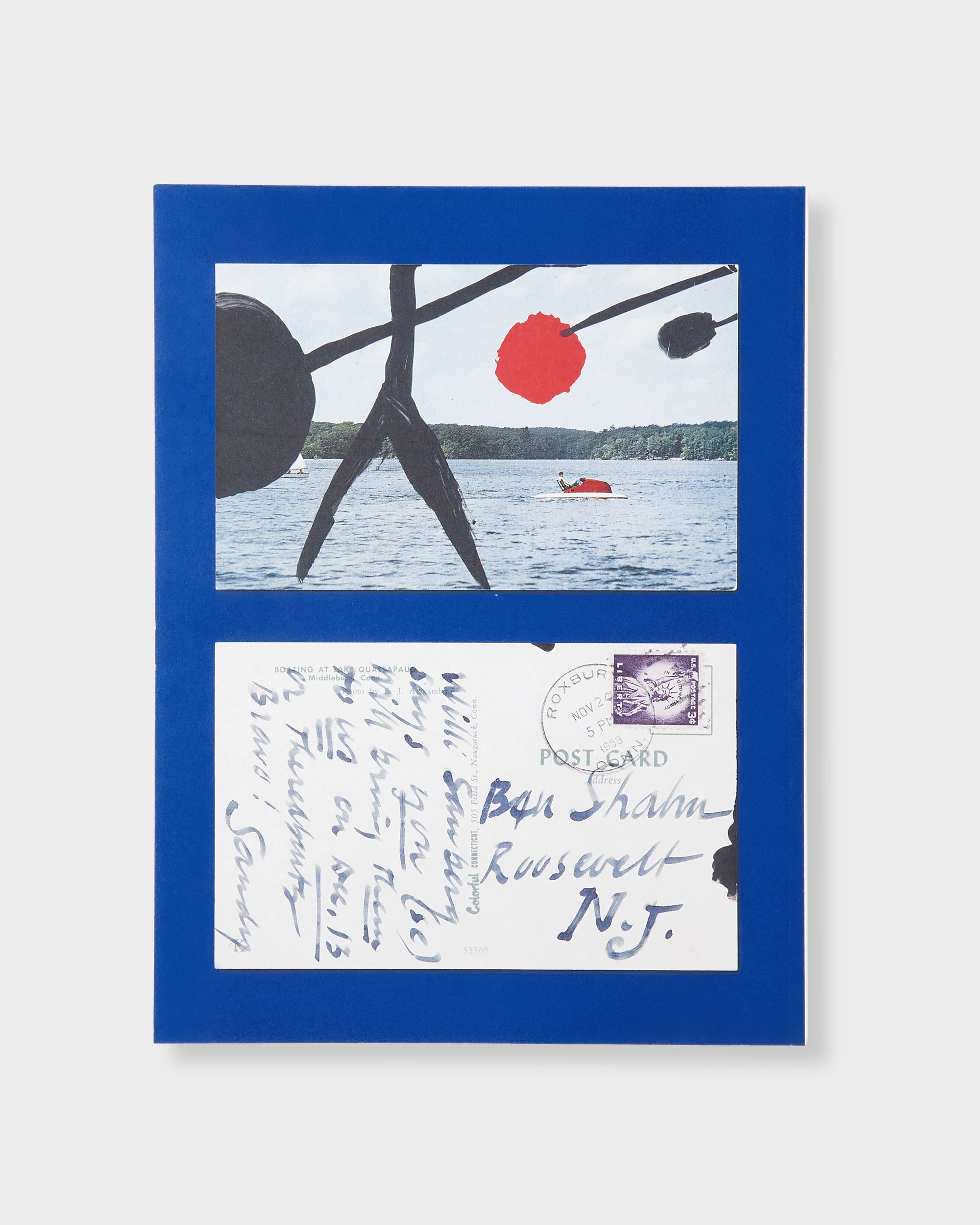

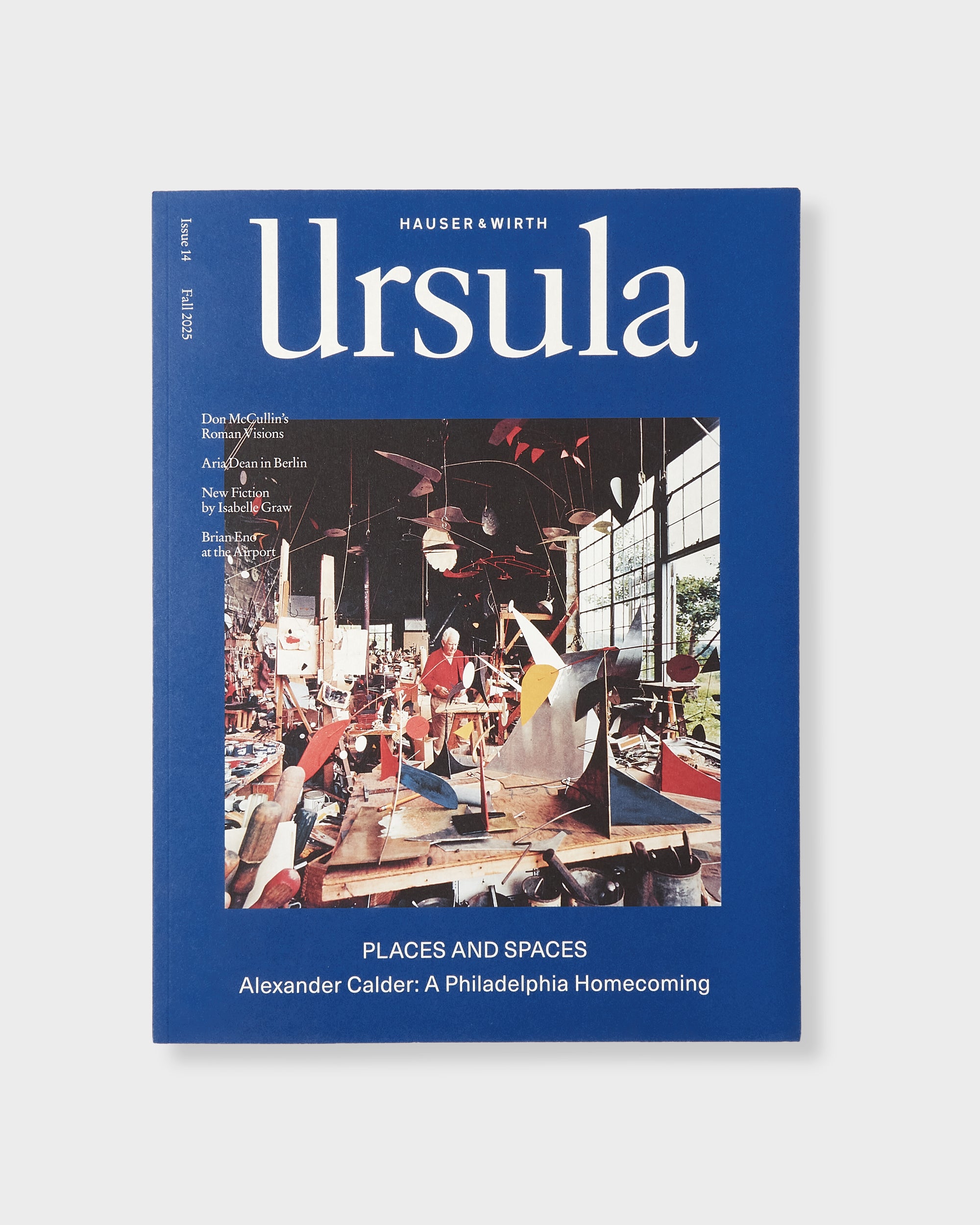

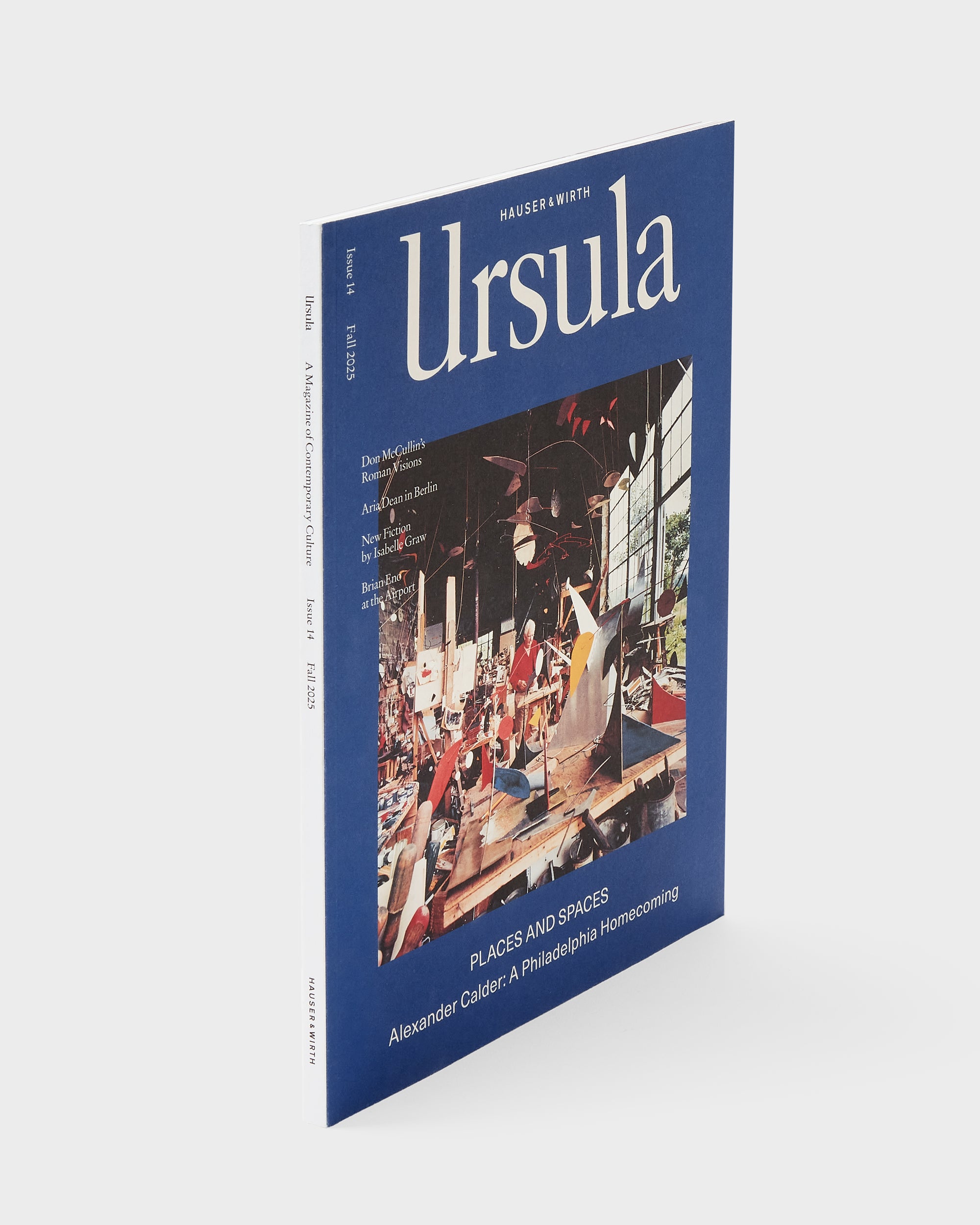

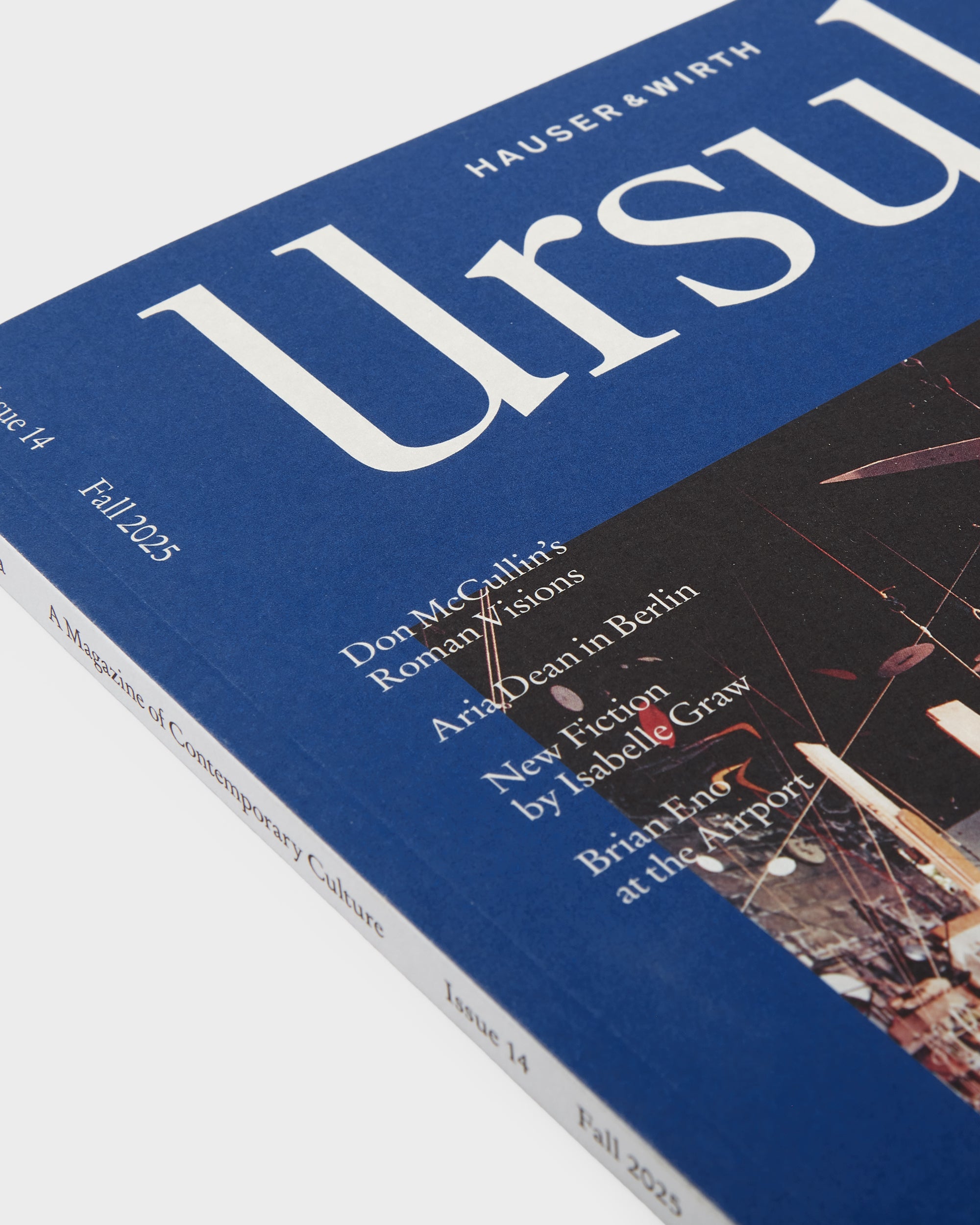

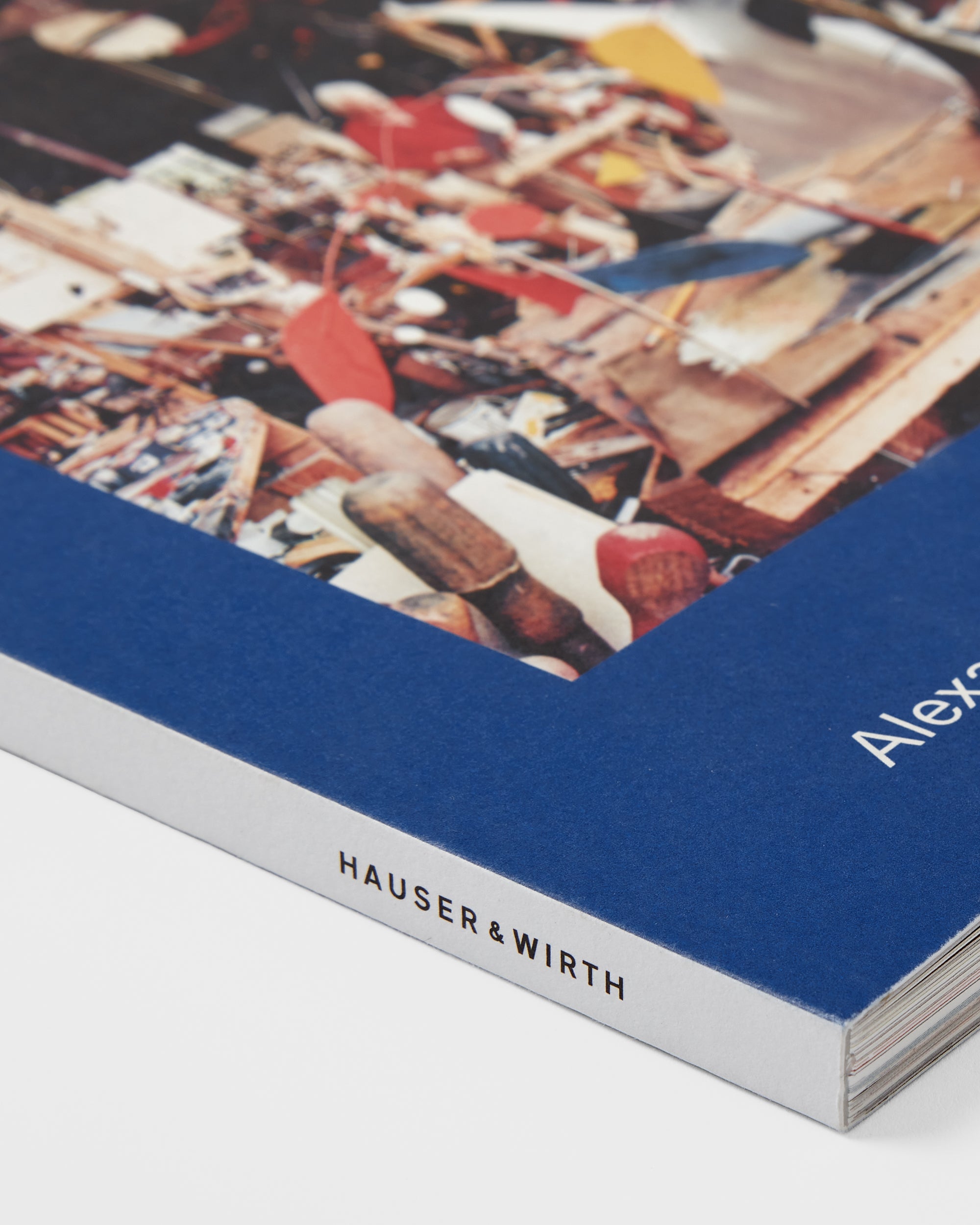

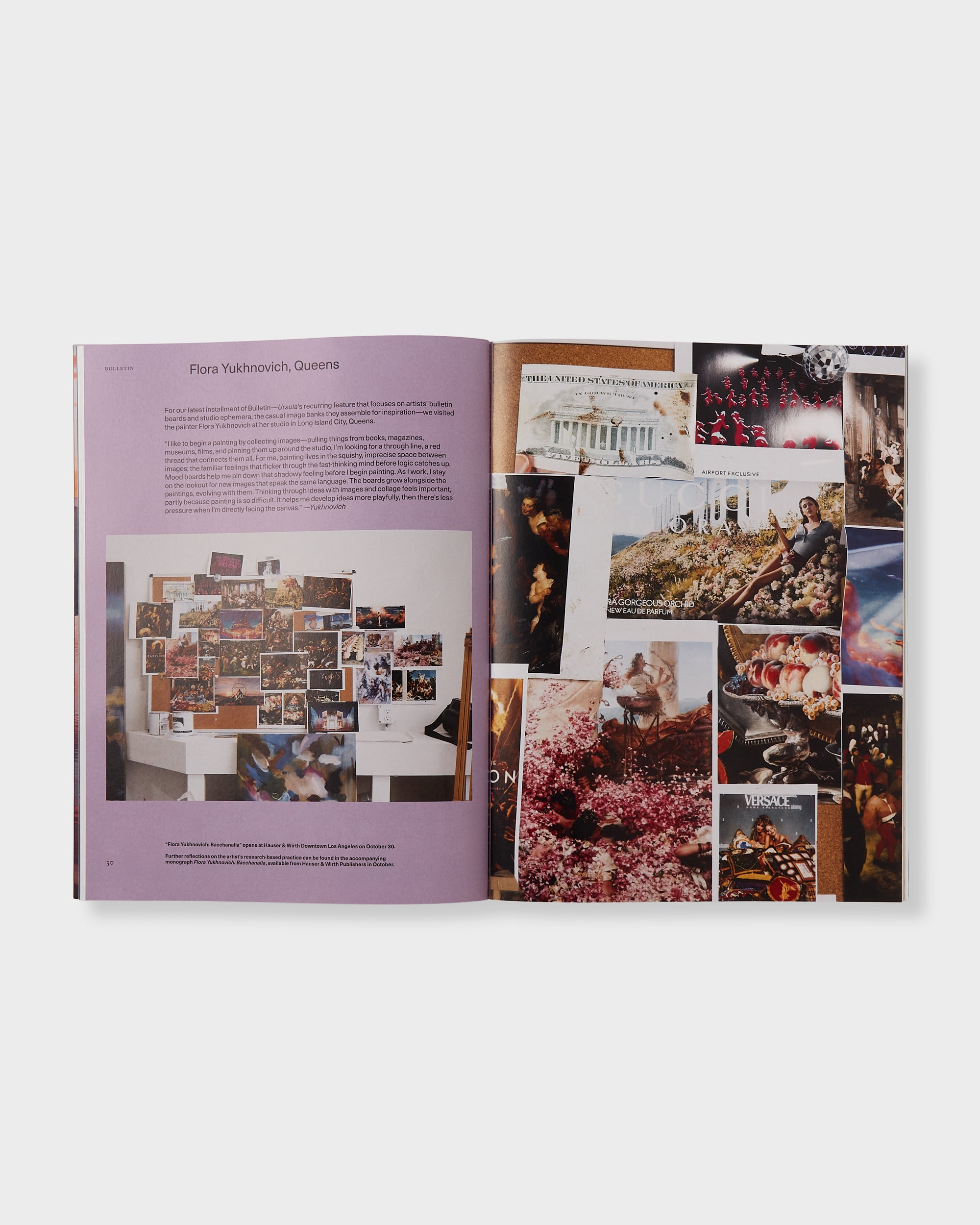

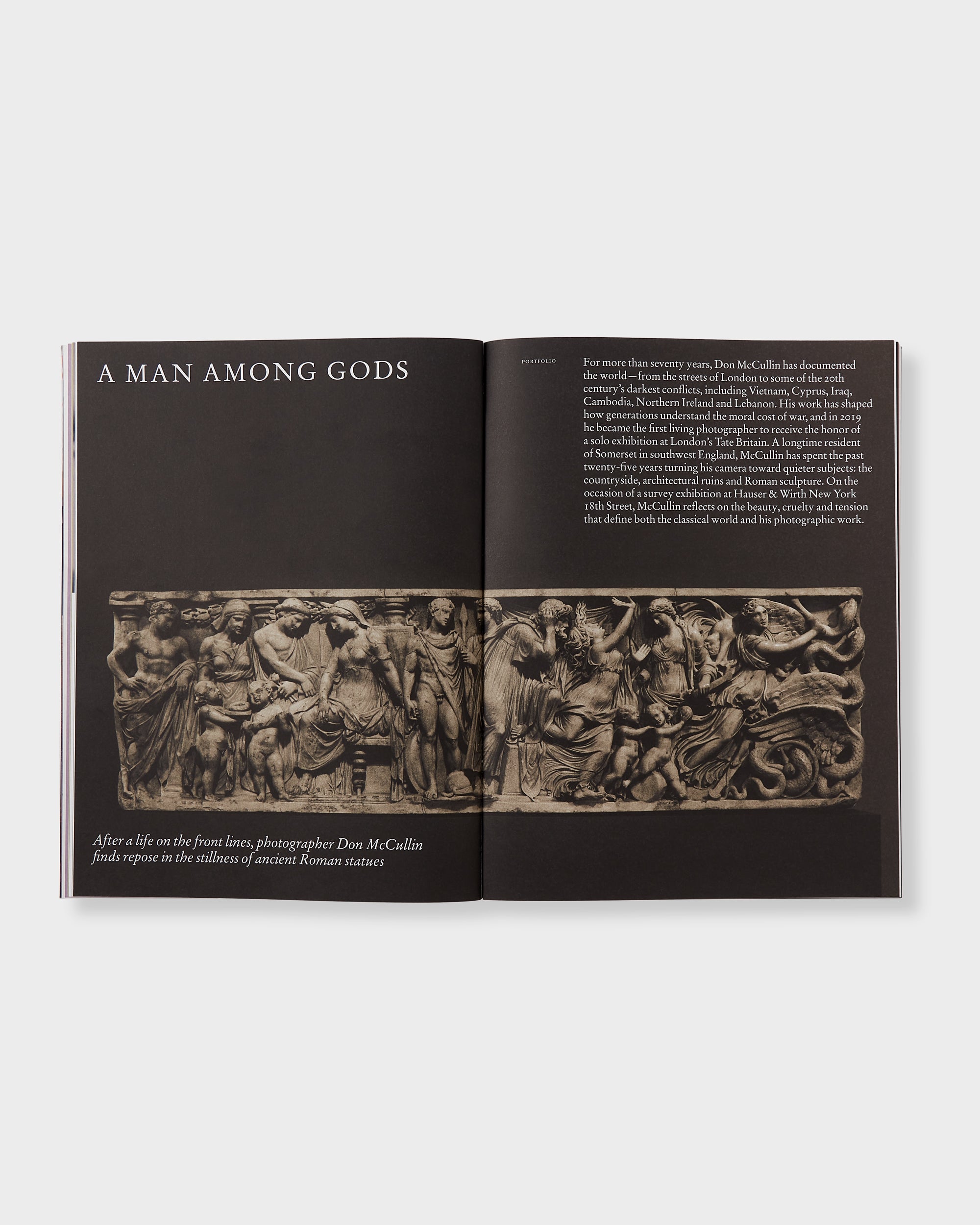

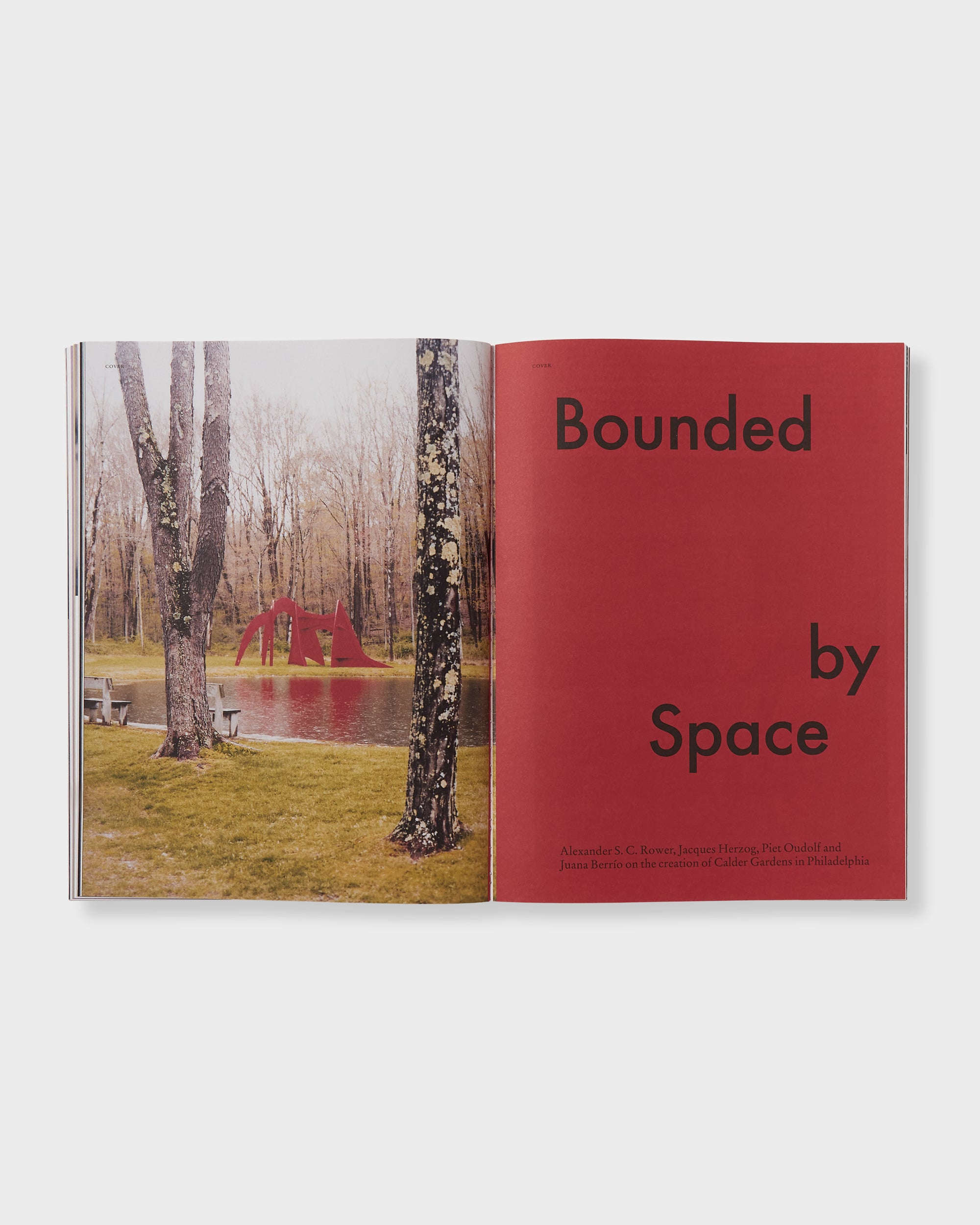

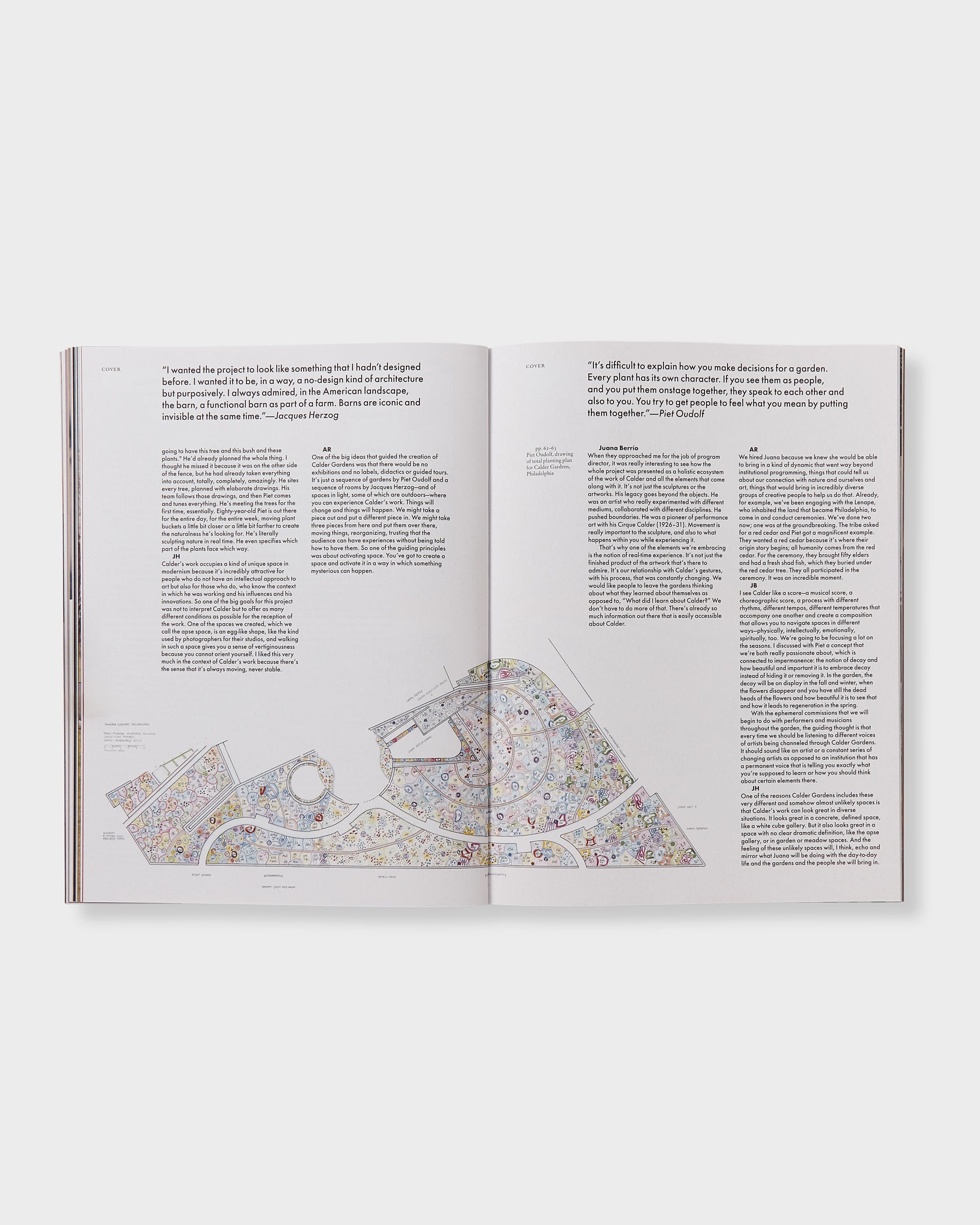

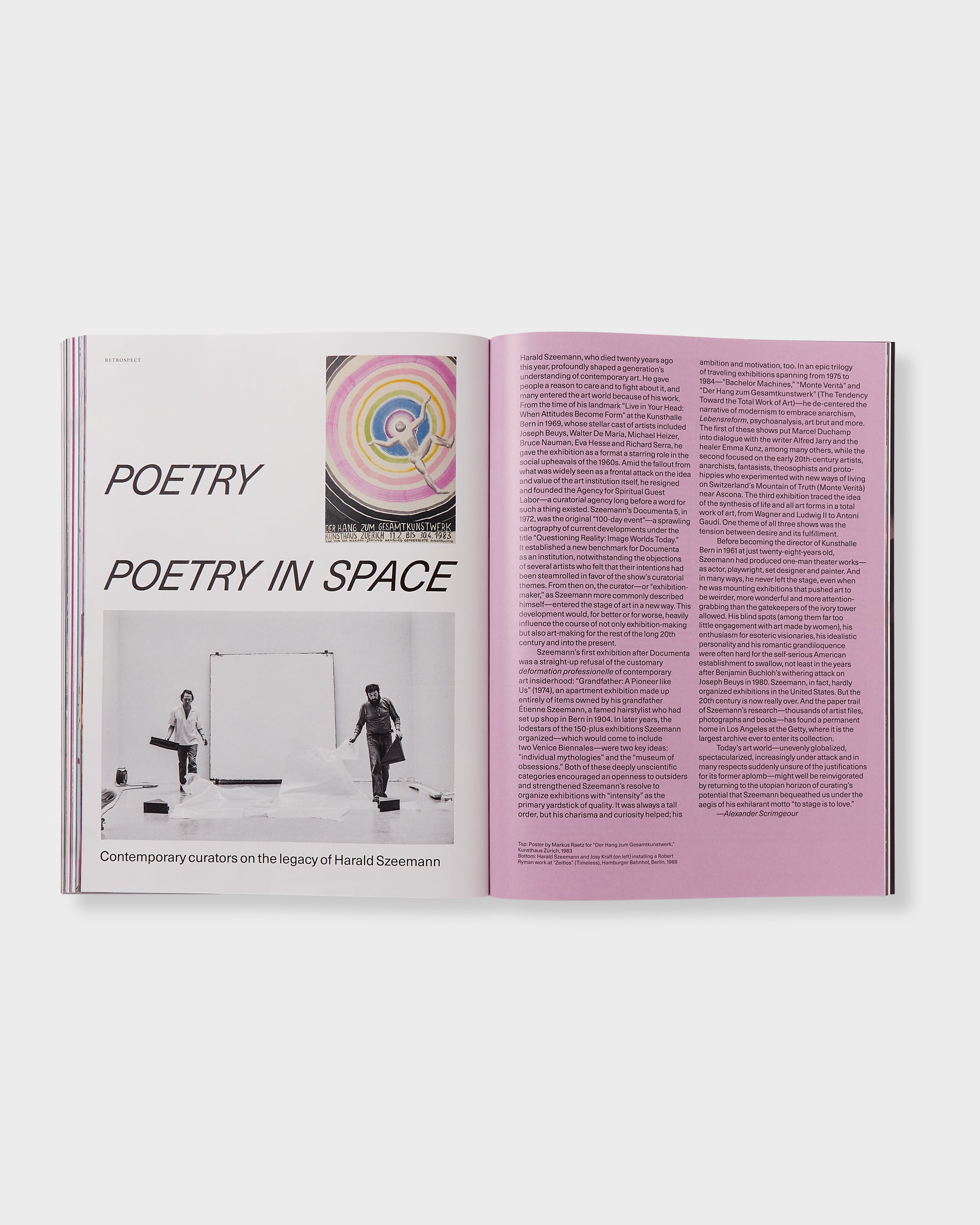

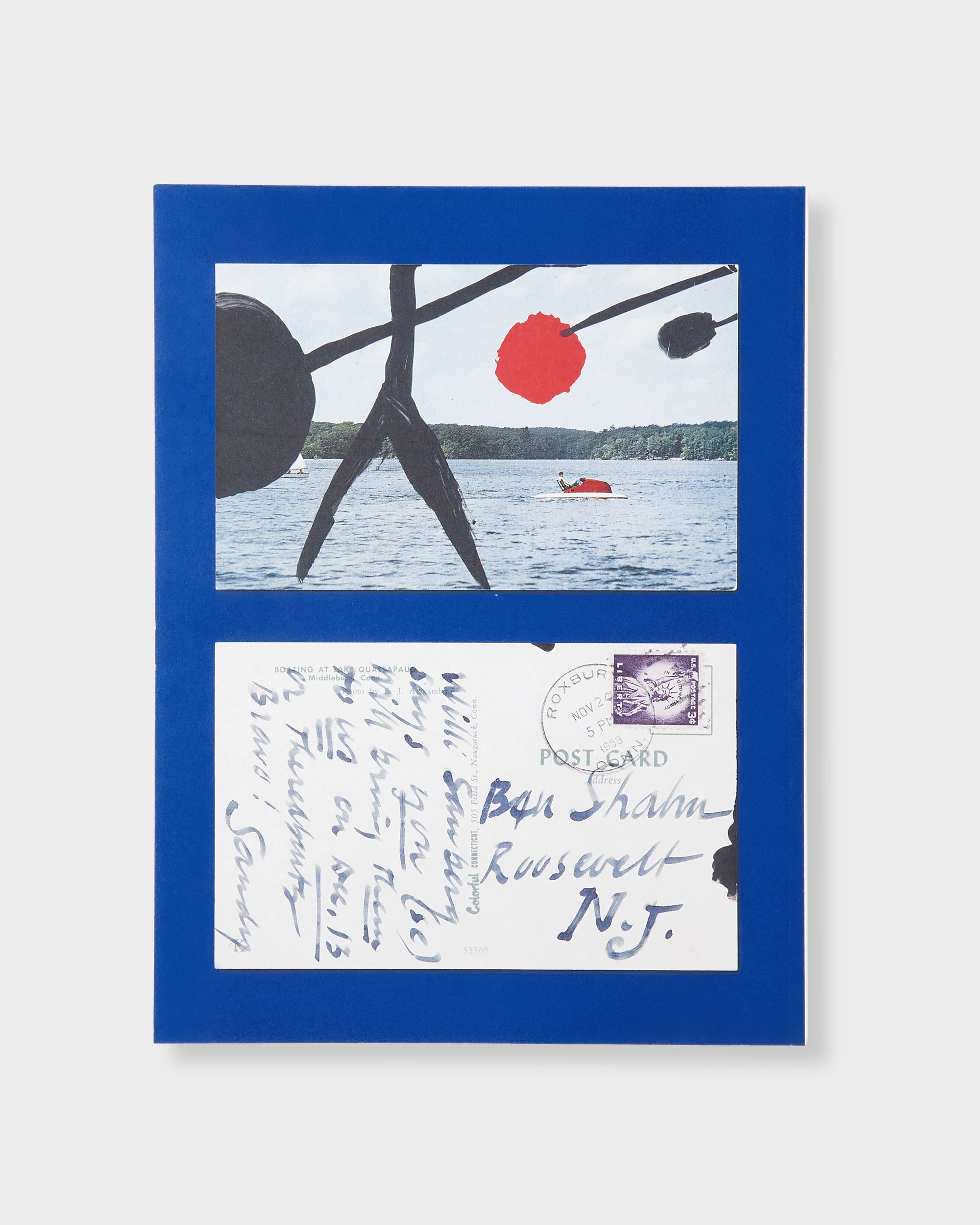

Ursula: Issue 14

Shipping & Returns

Depending on your location, items that you order may be shipped from the US or Europe.

We aim to deliver all orders within the UK / EU / US within 5 working days. Orders to be delivered to other destinations can normally be expected to arrive within 7 – 10 working days.

Shipping charges for all destinations will be calculated at checkout and included on your Order Confirmation.

For more information please review our Shipping & Returns Policy.

Choose options

Ursula: Issue 14

Sale price$30.00

Regular price

Explore more from

Ursula magazine